Cover photo by Alessandro Vannucci via Flickr

Series Introduction

This post is a part of a series introducing the recent anthology Invisibility in African Displacements (Zed Books 2020). The book was edited by Simon Turner and AMMODI co-founder Jesper Bjarnesen, and offers new analytical ideas for understanding migrant in/visibilisation. In each post, the contributors present their chapter in a more accessible format, either by selecting one empirical example or aspect or by relating their central argument to broader societal concerns or debates.

For an outline of the overarching idea behind the book, see the introducing blog post by the editors here.

by Lotte Pelckmans

Tabass is a woman from southern Niger. She figures in no statistics, no big databases or reports on migration, displacement or refugees. Nevertheless, over the course of her lifetime she will embody all of these movements. Tabass features in a documentary, which shows her involved in a heated discussion between three women on the continuities of slavery in Niger. During the discussion, she describes her own experiences of enslavement. You can see her in the documentary film here, at 56 minutes.

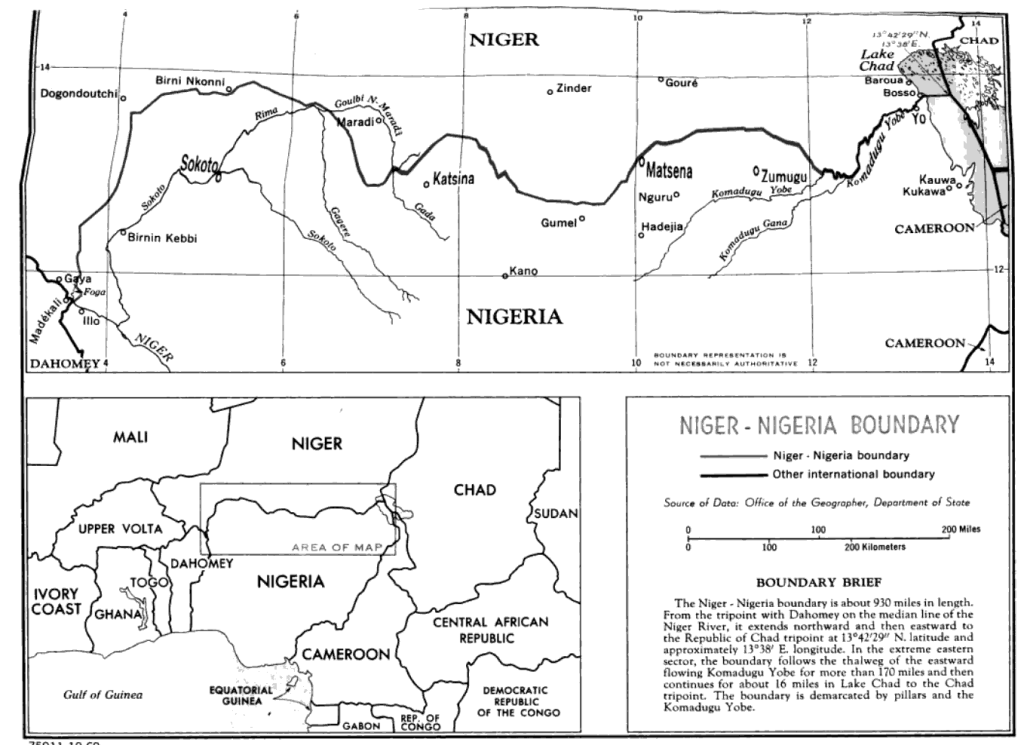

My chapter in Invisibility in African Displacements, entitled ‘Fugitive emplacements: Wahayu Concubine Visibility Tactics through Fugitive Cross-border Mobilities, Niger-Nigeria’ zooms in on the ways in which women with slave status who have been forcefully moved for marriage decided to move out. They thus flee from their forced marriage and from having been concubines. I argue that their flight is a way of ‘voting with their feet’, a form of refuge to protest against dire, unacceptable conditions. Their fugitive mobility expresses discontent with the dramatic continuities in historical forms of exploitation based on slave status in the post-slavery borderlands of Niger and Nigeria. By the notion of fugitive emplacements, I point to how these fugitive women gained new forms of belonging in a village hosting several wahaya refugees in Southern Niger, called Zongon Ablo.

Post-slavery in Niger-Nigeria Borderlands

Niger legally abolished slavery in 1905 and criminalized the discrimination and exploitation of people with slave status in 2003. However, as someone labelled of “slave descent” by her community, Tabass’ body still bears the daily burden of a cultural normalization of descent-based slavery. Niger is a post-slavery society, meaning that not only legacies but also continuities of African slavery have survived well after abolition. Tabass was forcibly moved from her home village in Southern Niger across the border to a compound in Northern Nigeria, a few hundred kilometres away, for a forced marriage.

Tabass had moved only a short distance and she did so alone. No statistics counted her, but her mobility moved her across dramatic social, cultural and emotional distances. Small distances can have big consequences. It is hard to count how many borders and boundaries Tabass was moved across as a bride: country, language, religion, culture, colonial history. She was moved from a former French to a former British colony, from a Zerma to a Hausa speaking community, from a rural village where women hardly veil themselves to an urban compound where she was highly secluded, and instead of moving into the role of a wife, she became a worker.

(E)motions

Emotions move people. They can be decisive in forced or voluntary movements, on small and large scales. Indeed emotions and feelings of affect (love, care, fear), can be drivers of mobility; they can set things in motion. However, some types of movement, related to large-scale, amplified events like war, disaster and terrorism, have gained more attention than others. Indeed, it is mostly crisis-related collective mobilities, generated by strong universal ‘emotions’ such as fear and physical threat that have been exposed, and in some cases made hypervisible, in migration studies and international media. In contrast, we do not often consider subtler movements driven by ‘softer’, individual and contextual emotions, such as the love for a child who is not at home; the need to move in with a partner in order to protect one’s status and/or virginity; travelling in order to care for sick loved ones.

Such ‘soft emotions’ also motivate people to move across both small and large spatial distances, but they are much less visible, because they are more individualised and often rather small-scale. A common example of such soft (e)motions is the way in which, in many societies, women have been married off and moved from one camp or village to another, maybe only 10-50-100 kilometres away. In this case, it is in the name of the emotions of love and care that they are moved or choose to move from one community/place to another. Such movements would not be counted as migrations or displacements and thus have remained largely under the radar in migration studies, unless they are abnormal, or more visible, spectacular and international (such as Thai brides in Denmark). Why are soft (e)motions driving small-scale mobilities/motions less worthy of description, analysis, or attention? The distances travelled may be short, and the brides may move one by one, not en masse, but the impact upon lives and the frequency of such marriage moves are high.

Questioning in/visibility

Invisible in big data and displacement statistics, the above-mentioned (e)motions are generally overlooked and neglected as important forms of migration/displacement. Movements related to marriage are a good example of such overlooked (e)motions, which do indeed move the women involved both physically and emotionally, but are rarely registered as an official migration from A to B. Emotionally, women are moved across social borders, breaking existing ties, changing their environment and altering their future life course: a displaced bride (such as Tabass) will hardly be in touch with her family and friends back home and is not supposed to return unless for special and important occasions. Her movement is an initiation into a new set of circumstances, not only in spatial terms, but also in the temporal, symbolic and social sense of becoming and belonging. After the move, the displaced woman becomes a wife, a daughter-in-law, a stranger that needs integration in terms of language, cultural and food habits, and maybe she becomes a mother, a co-wife and so on.

Which mobilities beyond the amplified dramas of disaster, beyond large-scale physical distances, and beyond the high numbers of people being pushed on the move in groups are worthy of our analytical attention? The emotional labour of moving for commonplace affective life events, such as the (micro-)moves of women for marriage which currently go under the radar, tell us just as much about the politics of households and families and the drama or joy of what it means to move.

Fugitive displacement and emplacement

Tabass fled her marriage out of protest, driven by emotions of fear and anger. In the chapter, I have defined her (e)motion as fugitive displacement. Similar movements of her peers have usually remained invisible, surrounded by silence and remaining under the radar of mobility studies. But while Tabass indeed almost certainly does not figure in a UNHCR or IOM report, or any other form of migration report or statistics, she exceptionally did gain some visibility and does figure in a small report, published in 2012, by a Nigerien NGO called Timidria that fights legacies of descent-based slavery in West Africa. In that report, she is defined as a wahaya, an Arabic term meaning “fifth wife”; a woman who has been forcefully married as a concubine to men with high status. She figures among the stories of eight other wahaya women who have been forcefully married.

Tabass was also filmed as a woman of slave descent who ended up in a village of refuge, called Zongon Ablo, in the documentary ‘Hadijatou’ by the Spanish documentary maker Lala Goma (see link to excerpt above). The visibility afforded to Tabass is exceptional and related to the advocacy and activism against legacies of slavery by the organization of Timidria who interviewed her. Tabass’ visibility is the exception rather than the rule and her fugitive displacement tells us a whole lot about the difficult fate, predicaments and strong emotions similar Wahaya – women in concubine positions in West Africa – have to navigate, cope with and act upon. Tabass chose to voice her discontent by fleeing towards a community of other fugitive people of slave descent in southern Niger. Upon her arrival, she tried to restore her dignity by recreating a family through emplacement, generating a new place of attachment and belonging. The hard emotional labour behind the different spatial moves in Tabass’ life deserve recognition and attention.

About the author

Lotte Pelckmans is an anthropologist interested in the crossroads between migration and slavery studies. She obtained her master’s degree from Leiden University, her PhD at the African Studies Centre in Leiden and has worked in Dutch, French, German and Danish academia. Her work focuses on mobilisation, conflict, social media, rights and the intersecting social and spatial mobilities of people with slave status, as well as anti-slavery movements in post-slavery West Africa and the West African diaspora. Based at the Centre for Advanced Migration Studies at the University of Copenhagen, she is currently working on social media and anti-slavery activism in the diaspora, and their intersections with Mali’s contemporary displacements related to descent-based slavery in Kayes for the SLAFMIG/EMIFO project.

Leave a Reply